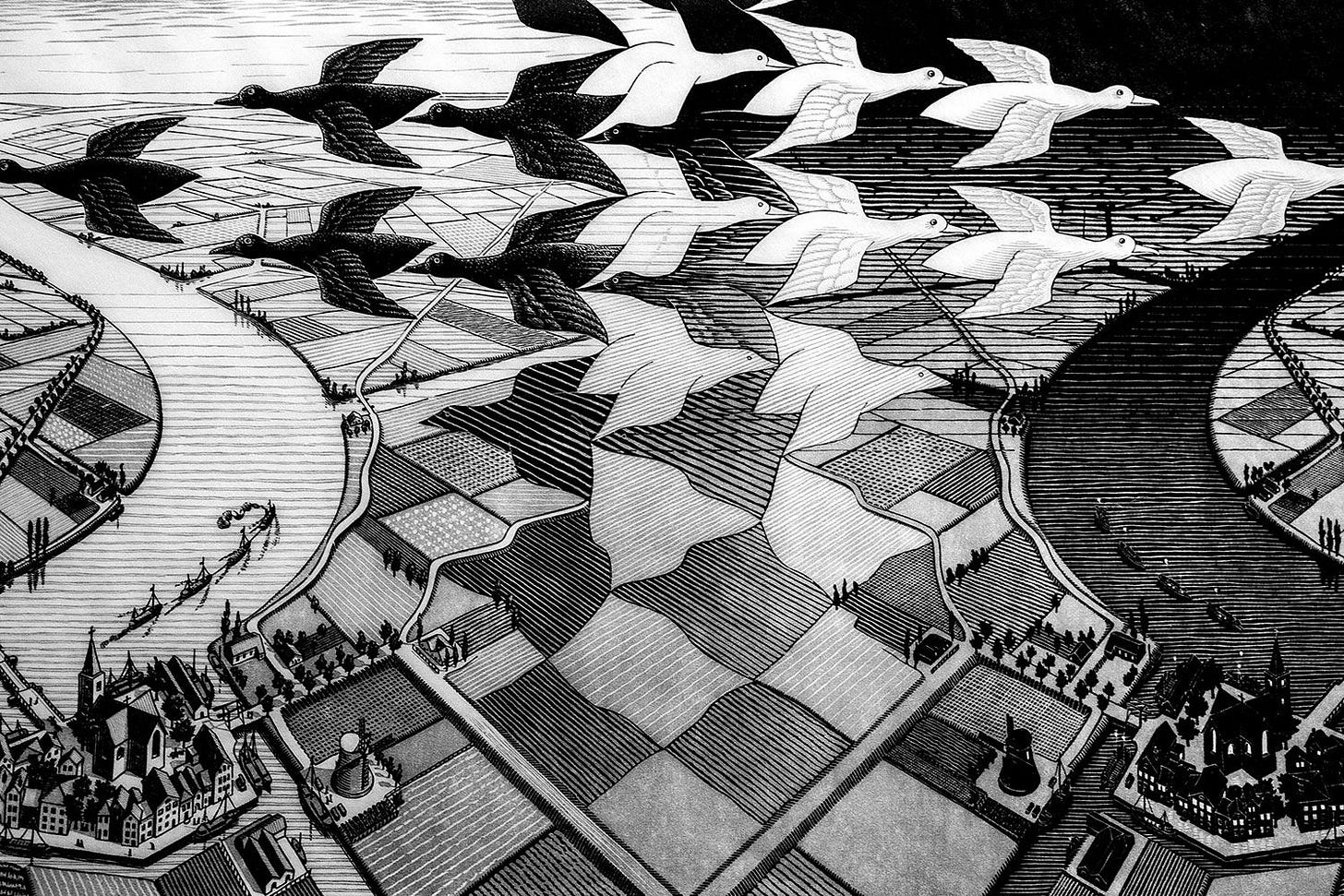

Two flocks of birds, ducks or geese perhaps, identical except for the fact that one flock is black and the other white, appear to take shape out of the dark and light spaces between them… What makes the image even more baffling to the eye is that the landscape and the birds also appear to emerge from one another, the birds and the world they soar above bringing each other into being. –The Book of Rain pp. 13-14.

[ID: the woodcut Day and Night by M C Escher.]

In this passage I tried my best to describe M. C. Escher’s famous woodcut Day and Night. In my first attempt I actually managed to get things backwards, by describing the white flock as situated on the left and the black flock on the right. Thankfully the sharp-eyed proofreader caught the error before the book went to print. My screw-up was simply more evidence that no matter how much I gaze at this image it continues to baffle me.

The website of the Escher in Het Paleis museum at the Hague provides some context for the woodcut:

As the basis for this metamorphosis, Escher used a tessellation. This is a motif whose outer lines connect seamlessly on all sides and can be repeated endlessly. Escher calls tessellation “the richest source of inspiration” he has ever tapped into. This print is an example of the new direction Escher took in his prints in the mid-1930s. The themes of eternity and infinity started playing a major role. Day and Night eventually became one of Escher’s most popular prints. He printed over 600 of these during his lifetime.

It's certainly possible to see themes of eternity and infinity in the woodcut, where it seems that these ambiguous shapes could go on generating themselves out of darkness or light endlessly. However, this isn’t what makes the image so mind-bending for me. It’s not the geometrical ideas behind tessellation either; anything to do with numbers makes my brain shut down. The theory behind the design is of no interest to me. It’s the undecidability of the image that bewilders and moves me.

In Escher’s universe you can’t have a black bird without the simultaneous emergence of a white bird. You can’t have either kind of bird without the landscape either, since the birds appear to form out of the ordered, mirror-image black and white rivers, fields, and towns below. Or perhaps the mirror landscapes below have formed out of the flight of these two flocks of birds. Are the white birds a representation of daylight coming to the night half of the world? Are the black birds a representation of the night coming to the day side? Would the painting be more accurately called Dusk and Dawn? No, it’s more mysterious and impenetrable than that. The white birds emerge from and/or create the night; the black birds emerge from and/or create the day. Or both at once. Can one even say that day is day without acknowledging that night exists within it, and vice versa?

But there’s something else going on here that has nothing to do with birds or the time of day. Any sort of foreground and background elements, not just birds and rivers, presumably could have worked to the same effect. I can look at the image endlessly and never manage to decide where each element begins and ends, because they are seamless and interdependent, and for an instant my rational mind overloads. For an instant I feel closer to apprehending what in Buddhism is called shunyata. Emptiness.

I’ve come across many definitions—and poetic gestures toward—this elusive concept. The thirteenth-century Japanese Zen master Dogen almost seems to have something like Escher’s own black-and-white imagery in mind when he says “The sun, moon, and stars resemble a rabbit and crows.”

But I always come back to Thich Nhat Hanh for his simplicity and directness:

We should practice so that we can see Muslims as Hindus and Hindus as Muslims. We should practice so that we can see Israelis as Palestinians and Palestinians as Israelis. We should practice until we can see that each person is us, that we are not separate from others.

Nhat Hanh reminds us that seeing this “emptiness” in things is not just a New Agey exercise in introspection but might actually be of crucial importance to all of us. The word “emptiness” in English has negative connotations, but for Nhat Hanh it means that nothing exists on its own. “We are empty of a separate, independent self. We cannot be by ourselves alone. We can only inter-be with everything else in the cosmos.”

Like one of Escher’s birds, there’s really no separating “me” from everything else. My mind makes the distinction between what I take to be “me” and “not me” but it’s a false separation, a trick the mind plays on itself. The result is that we turn our fear and hate outward, to that other out there, but really we turn it on ourselves.

Last week I talked about the final lines of Eliot’s poem “Little Gidding.” His imagery does something similar to what Escher does with visual ambiguity: the “last of earth” is also the beginning; the fire and the rose are one. Do I know what that really means? Not in any rational sense. I grasp at the sense of it and fall short. Eliot’s koan-like words take me only so far. Escher’s art takes me, it seems, just a little bit farther.

In the woodcut the myriad forms of things emerge from one another, and that is as far as I can penetrate into the nameless mystery of reality unless I’m willing and able to surrender my rock-solid sense of being an individual divided from everything and everyone else. I’ll likely never reach this state of perception, but I can glimpse it, just for an instant it shimmers there in Escher’s woodcut, what it might be like to be not just the observer but the birds as well, the day and the night, and the whole world all at once.

The quote from Dogen is taken from Dogen’s Extensive Record: A Translation of the Eihei Koroku by Dan Leighton and Shohaku Okomura. Wisdom Publications 2010.

Quotations from Thich Nhat Hanh are from The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching, Broadway Books, 1998.

How wonderful the Escher tesselation conjuring light from the dark now at the darkest time of the year!